The Faux 1000 Course Recon Ride

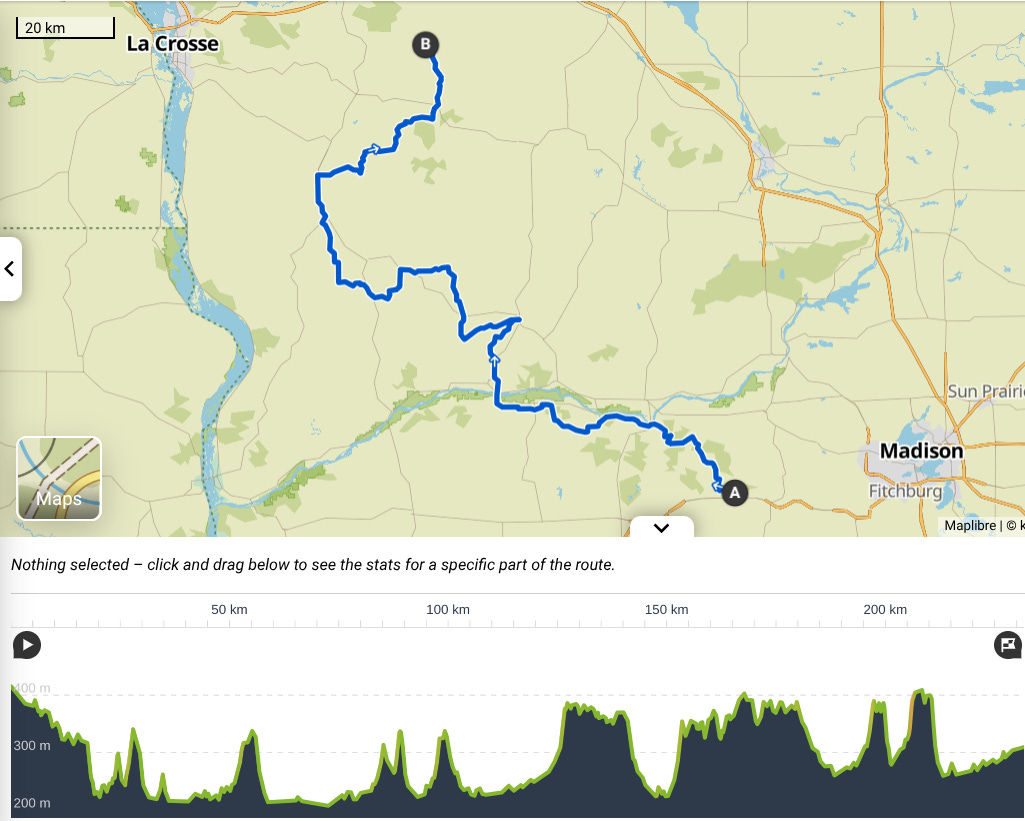

Remembering what it means to climb while checking out a Paris-Brest-Paris analogue route. Chicago flatlanders be warned.

Living in Chicago does curious things to you as a cyclist.

On the one hand, it will teach you how to output consistent power for hours and hours on end. As a corollary: it will quickly teach you exactly what’s wrong with your bike fit.

On the other hand, it will make you forget what it means to “ride a moderately hilly route.”

This isn’t a new revelation. Just a couple weeks ago I was writing about the Ten Thousand Ride, which is nothing if not a constant run up and down sharp hills. Part of the fun of that event is what a shock to the system it is for us Chicago cyclists. You get good at the things you practice, and in Chicago there just aren’t many opportunities to climb a hill, never mind fill a route with them.

This is, in part, why Chicago Randonneurs’ Regional Brevet Administrator Sarah Rice created “The Faux 1000” route.

Prepping for Paris-Brest-Paris

The oldest bike event in the world that’s still running is Paris-Brest-Paris, or PBP. It was raced from 1891-1951, and since then has been an exclusively amateur randonneuring event run every four years. It’s 1200km, and is exactly what it sounds like: ride from Paris to Brest and then back.

The route doesn’t cross any of France’s famous mountain ranges, of course, but if you look at that elevation profile, it’s a pretty relentless sequence of hills. The total elevation gain for the route is just over twelve thousand meters. Not crazy for the length of the event, but not much less than most cyclists in Chicago ride in a year. I’ve covered about 18k vertical meters in each of the last three years, for example.

(Compare that to the over 48k vertical meters I climbed in 2020 when I was still in Austria.)

The purpose of The Faux route, therefore, is to get cyclists ready for PBP by sending them on a route of similar length and hilliness.

Taking Things at a Casual Pace

While PBP may not be a race, it’s still ridden aggressively. The event has a 90 hour time cutoff, and for the last 13 editions the fastest rider has finished in under 45 hours. When Chicago Randonneurs runs The Faux as a brevet, it will have similar time limits.

In reconnoitering the route, however, Sarah and I were decidedly not trying to set any time benchmarks.

Instead, we split things into four days. Over (nearly) 1000 kilometers (more on the “nearly” in a second), that still makes for some full days of riding, but wouldn’t (for example) have us riding through the night. We opted for some planned camp stops and rode relatively heavy on camping gear, making it more of a bikepacking adventure than a randonneuring ride.

Our first day started with a train ride to Woodstock, Illinois, before setting off. We enjoyed a fairly strong tailwind for most of the day, and this being the flatter section of the route, cruised to 275km in just 10:32 of moving time, plus a couple hours of stops. That said, 275km is still a very long way, and after our final resupply we had about five of the hilliest miles of the day to get to our campsite. Not the way you want to roll into camp, but we managed.

Part of “rolling heavy” for me meant bringing my alcohol camp stove, which I intended to use for coffee and oatmeal each morning but ended up assisting my dinner as well as I heated up a pre-made pasta alfredo I’d grabbed from Kwik Trip. I don’t get to use this stove all that often, and while it was not a necessity for this trip, sometimes it’s just fun to use your gadgets.

Day two took us into the hilliest section of the course, advancing us from Barnveld, just a little ways west of Madison, Wisconsin, on a winding route up to Norwalk. Although none of the hills in this region are particularly large, they do come steep and usually one right after another.

Neither Sarah nor I have the best climbing legs of our lives right now, so as our pace dragged through the midafternoon, we made the decision to cut the day a little short. Originally, this was going to be our longest day of the trip, but we took the short side of the route’s final loop out of Viroqua and consequently rolled into camp around dusk instead of well into the dark of the evening.

Shout out to the tiny town of Norwalk, Wisconsin, by the way. We camped at their public campground right in town, complete with public bathrooms and showers.

Day three was, as planned, our lightest day of the trip, covering just 200 kilometers, though still with a decent amount of hilly up-and-down. This brought us back to Blue Mounds State Park, where we’d also camped the first night.

Day four went back out to nearly 250 kilometers, but despite a headwind for much of the day, a return to the flats (and a goal of an earlier train back to Chicago) got us rolling quick.

I realize that’s covering a lot more riding in a much shorter space than I normally do, but in this case I think the route is best taken in summary.

This is an excellent route. The recon served its purpose, and we marked a few spots to amend for the future, but nearly all of this route is ready for riding. The deeper it travels into Wisconsin, the more rural it becomes (and into Amish country for a while!), which is a very good thing in my book. The roads are small but friendly for bikes. They go climbing and winding through beautiful, hilly landscapes. The ascents are rewarded with roaring descents the likes of which I haven’t had the pleasure of riding since living in Salzburg. It’s the kind of route that makes you want to keep riding both because of and despite the challenge of the route itself.

And finally, as a preparation for PBP, it is an exceptional reality check for those (like me) who are all too used to riding flats. That’s not to say the route will overpower you. There are no hour long climbs at 10 percent grades. But it will stretch you, and that’s a good thing. It’s a route unlike almost any other in the Chicagoland area.

Sleeping Extra Cozy

Finally, I have to take a second to praise my newest (and newest favorite) bit of kit: my new Cumulus X-Lite 300 sleeping bag.

Damn, is this thing cool.

Or warm? It’s a 30 degree down sleeping bag that compresses down to a truly mind-bogglingly small size when packed. I’ve replaced two of my previous sleeping bags with this singular wonder.

Was it cheap? No. Was it worth the money? Absolutely.

I zipped myself into this thing and did not worry about the dropping evening temperatures once. It is already an indispensable piece of camping equipment for me. I spent quite a while scouring equipment manufacturers’ websites before settling on this bag, and it absolutely delivered. Pack volume is at such a premium on a bike, and this bag doesn’t give up a bit of performance in order to pack down as small, and usually smaller, than any other bag on the market that even approaches this temperature rating.